Cut the Cord in Enlightening Ways

The radio frequency spectrum falls roughly between direct current electricity and daylight. Boston University and Intel are among the research organizations targeting the high end of that range with R&D work that aims to provide wireless connections at speeds north of 1 Gbps.

The radio frequency spectrum falls roughly between direct current electricity and daylight. Boston University and Intel are among the research organizations targeting the high end of that range with R&D work that aims to provide wireless connections at speeds north of 1 Gbps.

The research has a variety of potential pro AV applications, including replacing copper, fiber, and 802.11 Wi-Fi for connecting digital signage components, projectors, and more. And despite their broadband speeds, some of the technologies could also be used for low-bandwidth applications, such as AV control.

The research falls into two categories. The first and perhaps more intriguing focuses on turning light-emitting diode (LED) bulbs into transceivers capable of supporting everything from low-speed control applications to HD video. Each bulb would provide a two-way, line-of-sight connection to one or more devices, with the range basically equal to the distance the light reaches.

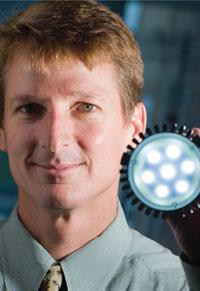

Boston University’s Thomas Little, associate director of the Smart Lighting Engineering Research Center, with a consumer LED light bulb. His team wants such bulbs to wirelessly communicate data.

“We envision each of those [bulbs] being like an RF antenna, communicating with objects underneath it,” says Thomas Little, a professor in Boston University’s Department of Computer and Electrical Engineering.

In the second area of research, Intel and a few dozen other companies, including Broadcom and Panasonic, along with schools such as the University of California Berkeley, are developing technologies for the 60 GHz band. Such technologies would enable connections between devices–say, a laptop and a projector–at speeds of at least 1 Gbps. But speed isn’t the only significant benefit. Devices built for the 60 GHz band promise immediate, automatic connections, the lack of which has kept Wi-Fi from growing beyond a niche play in pro AV.

“It’s key to get the user experience right when we’re talking about short-range, high-bandwidth wireless,” says Alan Crouch, general manager of Intel’s Communications Technology Lab in Hillsboro, Ore.

Speed of Light

Widely used in pro AV for applications such as arena signage, LEDs are slowly expanding into commercial and residential lighting. The main draw is that unlike incandescent bulbs, LEDs are highly efficient, wasting almost no energy in the form of heat. (For more information about how LEDs work, as well as some pros and cons in using them in pro AV applications, see “All About LEDs,” January 2006.)

The downside of LED bulbs for lighting applications is that they carry a hefty price premium over incandescent and fluorescent bulbs–costing $15 to $90 each. That’s mainly because they’re still relatively new, specialty products, just as compact fluorescent bulbs were earlier this decade.

But that premium could be offset by long-term energy savings and, in the case of the wireless communicating LEDs, by eliminating the cost of wired or wireless network technologies. For example, if the bulbs can eliminate the materials and labor required to run cables to a conference room projector or to digital signage displays around a mall food court, then the savings could be enough to make a business case for using the bulbs.

Or at least that’s how it’s envisioned to work. Little and the other researchers, who have collectively formed the Smart Lighting Engineering Research Center (http://smartlighting.bu.edu) with an $18.5 million National Science Foundation grant, are still hashing out both the technology and the business models.

Although the technology is still years from commercialization, the underlying concept of piggybacking data on light is a proven one. Wireless LED’s cousin, infrared technology, already can support up to 16 Mbps. Moreover, the researchers recently re-engineered an LED flashlight to support data at dial-up speeds.

“You could build this today with off-the-shelf components,” Little says. “It’s very doable.”