The Buzz: Installation Spotlight: The Sound of Green

May 11, 2009 12:00 PM,

By Jessaca Gutierrez

Point Park University, Pittsburgh

Sidebar

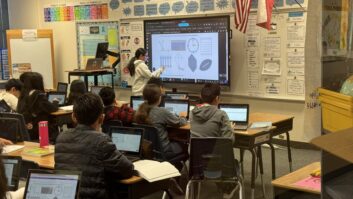

Dancer Alana Gergerich practices in Point Park University’s new LEED Gold-certified dance complex. When the university, which has one of the top dance programs in the country, decided to build the new dance complex, green design played a major role. A change from a central amplification control room to localized powered loudspeakers in each studio decreased materials, labor, and energy.

Photo: Cheryl Mann Photography

Pittsburgh is a far cry from the city that has, up until recent years, been known as The Smoky City because of the steel industry’s presence. Situated in the East End of the Golden Triangle, Pittsburgh’s downtown, Point Park University (PPU) is fast becoming a key player in the city’s effort to revitalize downtown and clear the air. When Point Park sought to build a new dance complex for what is one of the nation’s top preprofessional dance institutions, university officials had green in mind, but just how green took everyone by surprise.

“We started with presidential mandate to build at the very minimum a LEED Certified building. As we got further along, LEED Bronze was within reach,” says David Nash, principal of StoweNash Associates, the consultant on the project. “We broke ground thinking that we were going to be building a Bronze building, maybe Silver. In the end, it turns out that we achieved LEED Gold, the first of its type. Contrary to popular belief, LEED isn’t a dealbreaker. Because we started by embracing the LEED ideals, we were able to reach Gold status without a significant increase in budget.”

Although PPU’s dance program is one of the best—it’s in the same league as The Julliard School, University of North Carolina School of the Arts, and Indiana University—the old facility was substandard and a poor representation of the talent the school produces. A typical small dance studio would be at least 1200 square feet, and a midsize studio is about 2400 square feet. PPU’s dance facility only had two studios out of 10 that were midsize, and the rest were less than 1200 square feet, making it difficult to use the studios for the complicated dance moves the students perform.

“The AV complement in those studios was typically a home stereo with a CD player popped into it and a VCR and TV monitor on a rolling cart that would move from studio to studio, always getting there late or being double-booked,” Nash says.

The initial plan was to build four studios, which could be increased to eight in the future, with a centralized amplifier control room. Each studio would have local control and playback gear, but the control room would house the amplification system. But like all things, architecture and systems design is a process—what Design Principal Marty Powell from The Design Alliance in Pittsburgh calls a “patient search for a solution” that requires going back to the drawing board again and again. (See more of Powell’s insight at svconline.com.) It’s in that process, and the green-building analysis, that a new concept shook out. Instead of building a centralized space, the design would incorporate powered loudspeakers in each studio, allowing the AV to be localized to a studio and greening the design even more. This design also allowed for the addition of three more studios.

The Buzz: Installation Spotlight: The Sound of Green

May 11, 2009 12:00 PM,

By Jessaca Gutierrez

Point Park University, Pittsburgh

One of the new studios is a performance studio with its own theater seating system and theatrical lighting and rigging package. Here, they created a dual-mode system using a Biamp Systems Nexia PM DSP that allows the studio to switch between its daily operation as a dance studio, where the loudspeakers are working in stereo configuration, to a theater setup using a Midas Venice 240 24-channel mixing console.

Photo: Cheryl Mann Photography

Localized control may seem counterintuitive in an age where having one control sweet spot provides facility AV managers with an efficient way to monitor and control equipment. However, in this design, the Renkus-Heinz CF121-5B powered loudspeakers also used less conduit. With a control room, all the studios would have been wired back to this room, requiring a large amount of conduit to be snaked throughout the building. To overcome resistance and signal degradation, a heavy-gauge signal wire going from the loudspeakers to the control room would have been necessary. In addition, a dedicated supplemental cooling system would need to be installed in the control room.

“One of our biggest challenges in terms of the wiring was dealing with the damping factor for the subwoofers that in some cases were 100ft. or more away from the amplifiers. We were never really comfortable with that,” Nash says. “By going to the localized sound systems, we were able to eliminate all conduit except for stub-ups in the walls. We used plenum-rated cables instead of conduit-based. We were very pleased that the Renkus-Heinz loudspeakers and Bag End subwoofers both had onboard amplifiers that were rated for greater than 80 percent efficiency and emitted practically no heat.”

Because the heat load from the new design was smaller, no supplemental cooling system was necessary, decreasing energy usage. The cabling wire was also able to drop from 6-gauge to 22-gauge wire that would run a short distance from the rolling rack in each studio to the loudspeakers. Having nearly eliminated conduit, the team used multiconductor MC cables to distribute the power branch circuits from the LynTec motorized sequencing panel that allows the sound systems in the studios to be turned off remotely in the event of a fire alarm. In this way, the team saved on materials and labor.

“When you’re running conduit, you have to be very aware of how many bends you put in the conduit before you place a pull box or a junction box,” Nash says. “It’s a lot of fittings and a lot of custom-bending. The advantage of the multiconductor MC cable is that we were able to specify that cable to come preloaded with the desired number of circuits with isolated ground. The electrician never has to worry about bending radii or junction boxes. The conductors are already in the metal casing.”

To make sure the four loudspeakers provided the best coverage, the team plotted the spherical expansion of the acoustic pressure waves and positioned the loudspeakers in each studio. This is a departure from the historical approach of two loudspeakers situated at the front of the class, with students and faculty in front exposed to sound in excess of 85dB—which poses health risks such as hearing loss, laryngitis, and even vocal nodules and polyps—and students in back either pleased with the level or struggling to hear.

The Buzz: Installation Spotlight: The Sound of Green

May 11, 2009 12:00 PM,

By Jessaca Gutierrez

Point Park University, Pittsburgh

Working with Associated Architect and Acoustician John Sergio Fisher of John Sergio Fisher & Associates—based in Los Angeles and San Francisco—the team spent time discussing reverb time and how the geometry of the studio would almost guarantee flutter echo without proper acoustical treatment, as well as how to isolate external noise such as environmental background noise and sound migration from other studios. The team eventually established an NC rating of 25.

Related Links

The Buzz: Installation Spotlight: The Touch and Feel of Music

Modern society is never too far from its music, from cell phone ringtones to music-infused commercials to satellite radios to, of course, our MP3 music players. It’s only natural, then, that there should be a high-tech museum devoted to music…

The Buzz: Installation Spotlight: Commemorative Solutions

The newly opened Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Annex certainly has a New York flavor. Located in New York’s SoHo neighborhood, it’s mere blocks from long-gone…

Installation Profile: LEEDing the Way

The Bank of America (BOA) Tower sleekly shoots 1200ft. above the traffic heading uptown on Manhattan’s Sixth Avenue…

These discussions also eventually led to selecting Bag End PS18E-IF4 powered subwoofers, two in opposing corners of each studio. The subwoofers had to be custom-configured so that they could be installed in a non-traditional down-firing position, which Bag End accommodated, along with placing hanging hardware on the back of the cabinets. Coupled with the two adjacent walls, the subwoofers capitalized on the diagonal room dimension to accommodate the long wavelengths.

“The end result is that a wonderful combination of room shape, acoustical treatments, choice and locations of loudspeakers and subwoofers has yielded superior sound delivered at much lower and healthier levels than were experienced in the older existing studios,” Nash says. “Everybody loves the richness of the sound in the studios. The Bag End product is flat down to 8Hz. Instead of the chest-thumper experience that you get from a typical subwoofer, which again we felt was not appropriate for these rooms, we get a nice, warm, and rich low end that’s delivered at a much lower sound level.”

One of the new studios is a performance studio with its own theater seating system and theatrical lighting and rigging package. Here, they created a dual-mode system using a Biamp Systems Nexia PM DSP that allows the studio to switch between its daily operation as a dance studio, where the loudspeakers are working in stereo configuration, to a theater setup using a Midas Venice 240 24-channel mixing console. The Nexia switcher only gives the faculty “caveman” controls—that is only the necessary controls instead of a complicated plethora of controls.

“One of the problems that we and our colleagues and peers have experienced within the last decade is the move toward removing controls from face panels in favor of accessing them digitally or through a remote control,” Nash says. “It’s problematic in that in a dance studio, a dance teacher shouldn’t be a technician. A dance teacher should be focused on the students and delivery of the curriculum. So a rackmount mixer with a dozen knobs on the front is just a recipe for disaster. Many times we’ve recommended against a client going with a rackmount mixer with lots of knobs. Invariably it’s pulled out, or the knobs are taped over within months.”

That said, those managing the project eventually selected the Biamp product because it would provide a digital signal processor that could allow multiple inputs to be managed, but it wouldn’t give the user—the faculty—too many control knobs on its front panel. Instead, in conjunction with a voltage control module, they can only adjust the volume, bass, or treble. Everything else—source selection, compression, and limiting—is happening behind the scenes.

This outfit in the new complex has been so successful that existing studios in the older portion of the university’s dance program will be retrofitted with the same system.

The Buzz: Installation Spotlight: The Sound of Green

May 11, 2009 12:00 PM,

By Jessaca Gutierrez

Point Park University, Pittsburgh

Architect’s Perspective

In the new portion of the Point Park University dance complex in Pittsburgh, achieving Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Gold meant a collaborative design process that didn’t end when the school broke ground on the project.

“Architecture is a search for a solution. You start with a vague idea of the needs, but as you begin to draw and imagine the use of the building you learn things,” Powell says. “And in the process, I think we learned that there were better ways to solve problems than what we initially had as a concept. It’s a fiction I think of the movies about architects that you have an inspiration and that is the building. In fact, it’s a patient search for a solution that is drawing things over and over and over and over to get an end product.”

To really tap into what faculty and students needed in the new dance complex, Powell and team went through a process they call “The Day in the Life.” As part of this technique, David Nash, principal of StoweNash Associates, the consultant on the project and a knowledgeable resource on the dance life, walked the architects on the project through a day in the life of a dance teacher, student, and a visiting master-class dancer. By understanding how they enter the building, where they change their clothes, where teachers teach their class, and where they have follow-up sessions, the architects were able to more easily understand what was needed from the building.

“[This] helped us to begin to understand that maybe flexibility and decentralized controls would be better for the university and all its constituents, teachers, students, guests, parents,” Powell says. “There was just too much to anticipate, and if you can make it flexible, then you don’t have to anticipate,” he says. “It’s not like game time at the University of Kansas where all eyes are at one place—all eyes are all over the place. It is the evolution of a concept that drives problem solving. It’s testing ideas and testing concepts, finding out what works best, rather than having a fully formed working idea in the beginning.”

Going through this process is a crucial part of the design, and it’s almost as important as the final product, Powell says.

“You start with concepts, and those are very rough ideas, and then one or two ideas seem to make sense, and then you do what are called schematics—a little bit more detailed. You begin to understand the engineering systems, but they’re still pretty sketchy and there will be maybe two or three schematics,” Powell says. “And typically, one or two of those schematics makes sense, so you do what are called design development drawings. You develop more detail and you add even more engineering systems, but it’s still very design oriented. Of course, code and ideas about products are there, but only after the design development do you begin to do the construction working drawings. But even with the construction working drawings, which are the heart of the project, you’re learning what will work and what won’t work because manufacturers are very much part of the project.”

In the dance complex case, that process led from a centralized control room to localized powered loudspeakers. It was a design solution that came about from collaboration between the architects, consultants, and integrators.

“Systems are better integrated if the architect understands the requirements of the system, and then the systems designer understands the requirements of the architecture,” Powell says. “The end result is better. Rather than a narrow focus, my advice would be to have a wide focus for the context of the systems.”

—JG