Today I focus narrowly on Versatile Video Coding (VVC) and it's potential for commercial success. For additional background, take a look at my article, How to predict codec success--I identified nine questions that reveal the critical factors that will largely dictate if and when a codec will achieve commercial success.

With that in mind, I’ll apply those questions to Versatile Video Coding (VVC), a standard-based codec that was finalized in July. I suggest that you at least scan the codec success article before reading this one.

One of the questions I do not consider is the technical innovation deployed in the new codec. So, if you want more about the technical foundations of VVC, check out this article. I’ll jump right into the questions.

Audio + Video + IT. Our editors are experts in integrating audio/video and IT. Get daily insights, news, and professional networking. Subscribe to Pro AV Today.

1. What’s the codec’s comparative efficiency?

Obviously the codec’s comparative efficiency dictates how much bandwidth saving the codec can deliver, one of the key benefits. Compared to HEVC, the ITU-T press release promises that “VVC will need only half the bit rate of its predecessor 'High Efficiency Video Coding' to achieve the same level of video quality for high-resolution video content.” Qualcomm is a bit less optimistic, stating that “VVC...offers a 40% reduction in file size compared with the previous standard, HEVC, while maintaining the same level of video quality.

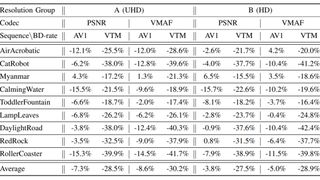

The most recent white paper on the topic is Comparing VVC, HEVC and AV1 using Objective and Subjective Assessments. Table III, shown below, presents two of the most relevant test cases considered by the researchers, UHD and HD video, and compares AV1 and VVC (called VTM in the table) to HEVC using two objective metrics, PSNR and VMAF.

- How to understand low-latency streaming solutions

- Live streaming comparison guide

The Average line on the bottom tells the tale. Reading from left to right, using PSNR as the metric, AV1 produced the same quality as HEVC with a data rate reduction of 7.3%, while VVC (again, VTM) delivered the same quality at a reduction in data rate of 28.5%. Scanning all the VTM results, they average slightly less than 30% as compared to HEVC.

These findings don’t disprove the ITU-T or Qualcomm results, since codecs generally improve their performance over time. Still, the proven benefit today seems closer to 30% than 50%, which is significant but not groundbreaking.

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

As I observe in the Nine Questions article, “the vast majority of new codec deployments are not to harvest bandwidth savings or other delivery efficiencies. Only tip of the pyramid publishers like Netflix, Facebook, and YouTube have deployed VP9, despite it currently being about 35-40% more efficient than x264. Rather, publishers typically adopt new codecs like HEVC because it opens markets for new customers.”

This is a great lead-in to question 2.

2. What new markets or platforms does the codec enable?

Looking back, H.264 was very quickly deployed by streaming publishers because it enabled delivery to mobile devices, which the previous codec, VP6, didn’t. Similarly, most of the publishers that deploy HEVC do so to send 4K SDR/HDR videos to SmartTVs, a market they couldn’t affordably serve with H.264.

As we’ll discuss in a moment, VVC is at least 2-3 years out from meaningful deployments. Perhaps at that time 8K or VR will be new and compelling markets, though it’s generally acknowledged that without high dynamic range, 4K video is tough to distinguish from HD in most configurations. Best case, at this point, we just don’t know if VVC will enable any new markets or not.

3. How is encoding time?

Encoding time translates directly to encoding cost; the more it costs to encode with a codec, the harder it is to achieve breakeven from bandwidth savings, particularly with distribution costs (in costs per GB) continually dropping.

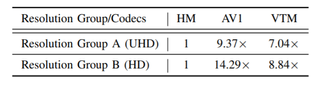

The white paper compared VVC (again, VTM) and AV1 encoding times to HEVC normalized to 1.0 (HM in the table), and produced the results shown in Table 2. Here, you see that VVC takes between 7-9 times longer to encode than HEVC. If you run your own encoding farm, this means that VVC will be 7-9 times more expensive to encode than HEVC. If you use a service provider, expect a similar price increase.

I should note that the white paper’s observations about AV1 were based on AV1 version 1.0, and in May 2020 AOM released AV1 version 2.0. While quality improvements were minimal, AV1 is a much faster encoder at this point. So, while the white paper’s AV1-related quality observations are probably still on-point, the performance-related observations are likely outdated.

Along those lines, you should also expect VVC encoding to become more efficient over time, and not remain at 7-9x HEVC.

4. Can VVC be implemented in software on relevant platforms?

Probably not. As we all personally know, battery life is king when it comes to mobile use. From a decoding complexity perspective, VVC is between 1-2x more complex than HEVC according to this study, and requires 167% of the decoding time of HEVC in this report.

So, while VVC may be playable on computers (more on this in the next session) without hardware support it won’t probably won’t be deployed to mobile devices until hardware decoding is available. The rule of thumb for hardware support is one year after the codec is finalized for chip-level products to become available, and another year for end-user products based on those chips to hit the market.

That means Fall 2022 for mobile support in hardware, best case. Ditto for SmartTVs and OTT/STB devices, which won’t have hardware support until then either.

5. Does the Alliance for Open Media (AOM) support the codec?

Probably not. The Alliance for Open Media members are software developers, chip and device manufacturers, content companies, and service providers that together developed and launched the AV1 codec. Since Google and Mozilla are both members, their respective browsers, Chrome and Firefox, have long supported AV1, but neither supports the HEVC codec even on platforms where the operating system already supports the codec.

This is a subtle but important point; Google and Mozilla could probably support HEVC on systems with existing hardware HEVC support without incurring a royalty since that’s how Mozilla supports H.264 on some platforms (see here for more details). Systems with HEVC support include all new Macs and Apple devices, many new Windows computers, and most new Android devices. However, you can’t play HEVC in Chrome, Firefox, or Edge for that matter--Microsoft is also an AOM member-- because none of these companies have added support for this hardware.

It’s hard to imagine that any AOM browser developer will extend support to VVC. So, even though VVC could probably play without hardware support on computers and notebooks (where battery life isn’t such a big issue), lack of support within Chrome and Firefox will complicate playback on these devices and discourage adoption.

6. Is the codec a MPEG standard?

Yes, and this is generally a good thing. But after the royalty debacle that discouraged HEVC support, it’s hardly the guarantee of codec success like it was for H.264 and MPEG-2.

7. What’s the technology ownership and monetization model?

The cleaner the technology ownership and monetization model, the easier the ultimate licensing cost is to ascertain. VVC is a true MPEG codec developed by dozens if not hundreds of contributors, and their development efforts will be monetized via licensing.

As you’ll read about in the next section, this means that it may be awhile before we know the VVC royalty structure.

8. How set is the royalty structure?

At this point it’s completely unknown. Understand that before the launch of the HEVC codec, many companies committed to supporting new hardware codecs before the royalty costs were known because they assumed costs would be reasonable. That changed with HEVC which is still a mess. So, it’s expected that larger manufacturers like Apple and Samsung will resist supporting a new codec until the royalty structure is clear.

In 2018, an industry group called the Media Coding Industry Forum (MC-IF) formed to help VVC IP owners formulate a more cohesive and reasonably priced royalty for VVC. In July 2020, the MC-IF launched formal “patent fostering” efforts to help form a single patent pool for VVC. However, one of the three HEVC patent pools administrators, HEVC Advance, recently announced their own proposed VVC licensing program, which was seen as an attempted preemptive strike by at least one other pool administrator.

Best case, the patent fostering process would lead to the selection of a patent pool administrator (or administrators) by late 2020, but there are no guarantees. So, at this point, the royalty structure is unknown and the prospects for a single pool are in doubt.

9. Is there a content royalty?

Ditto. We don’t know at this point.

What’s this all mean? Best case, given the 2-year hardware cycle between when a codec is finalized and when it appears in consumer products, it will be 2022 until devices with VVC decoding hit the market, and that will be dribs and drabs. It will take much longer for the installed base to reach any relevant critical mass. And this adoption may be delayed until the royalty picture is set, which likely won’t happen until mid 2021.

If you’re a streaming producer worried about missing the boat on VVC, file that concern in the “worry about in 2022” file.