Immersed in the Work of 3D Visualization

As Scott Robinson watches the video of a surgeon delicately cutting the pericardial membrane while the patient’s heart beats away, there’s only one thing on his mind. ?If I were having this procedure, I’d really want my surgeon to have a good view of depth,? Robinson says.?You go a little too far, and it’s game over.?

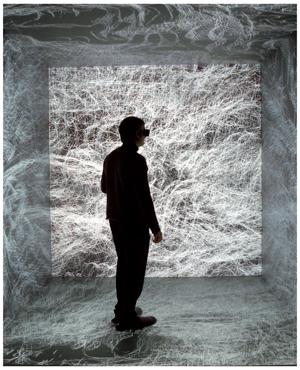

Immersive virtual reality environments, such as this one by Barco, allow expert teams to conduct scientific and medical research in 3D to accelerate the development of advanced procedures and treatments.

Credit: Courtesy Barco

AS SCOTT ROBINSON WATCHES the video of a surgeon delicately cutting the pericardial membrane while the patient’s heart beats away, there’s only one thing on his mind. “If I were having this procedure, I’d really want my surgeon to have a good view of depth,” Robinson says.“You go a little too far, and it’s game over.”

Robinson’s company, Beaverton, Ore.–based Planar Systems, is one of several manufacturers looking to leverage the need for precision by offering three-dimensional (3D) visualization systems, which provide the depth of view surgeons increasingly value when performing laproscopic surgery and other procedures involving a camera. The catch: Although there are obvious benefits, hospitals and physicians’ groups still want hard proof before shelling out several thousand dollars (and often far more) for 3D displays and their supporting technology.

In an effort to convince health care professionals of the solid business case for 3D — such as faster, more accurate diagnoses and less risk of malpractice suits — Planar recently participated in a clinical trial at Emory University in Atlanta, where radiologists viewed more than 1,000 digital mammograms using 2D and 3D technology.

“They found that the 3D view has reduced false positives by something like 49 percent and false negatives by 40 percent,” says Robinson, product manager of stereoscopic displays at Planar. “What we’re seeing in the medical market is that we need to go through some of these clinical trials and give evidence that not only does a stereoscopic view not do any harm, but it also enhances, for example, a radiologist’s diagnosis.”

SLEIGHT OF EYE

Today’s 3D visualization systems can be divided into two types: those that require special glasses or goggles to see the image (stereoscopic) and those that don’t (autostereoscopic). Autostereoscopic systems use a variety of techniques to create the depth and other attributes that, with the help of the viewer’s brain, combine to create the perception of a 3D image.

“They have some tricks for blocking some pixels for the left eye and blocking others for the right eye,” says Jennifer Colegrove, senior analyst for display technology and strategy at iSuppli, a market research company based in El Segundo, Calif. “So your left eye and right eye see slightly different images. Then your brain combines them to view a 3D image.”

Choosing between autostereoscopic and stereoscopic comes down to a variety of factors, such as how many people are going to be viewing the 3D image at the same time. In automotive design, some users maintain that stereoscopic isn’t always a good fit.“The design process is a very social process,” says Jeff Nowak, head of the digital design studio at Ford Motor Co. in Dearborn, Mich.“It’s about a bunch of different groups coming together. That’s difficult to do when only one person can put on a headset.”

That concern crops up in some of 3D’s other key markets as well. For example, Robinson says some of the surgeons he’s talked to have indicated they don’t like feeling isolated from everyone else in the operating room. “You can’t be collaborative with head-mount displays,” says Robinson. “So we’ve started offering our monitors for that market.”

Autostereoscopic displays have their downsides, too. Viewers often have to keep their heads in a “sweet spot” — the place in front of a display where the 3D effect is at its maximum. That requirement can be an issue when, for example, the application involves multiple people viewing the display at the same time.

VIEWS THAT DON’T COME CHEAP

The total market for 3D visualization systems will grow about 19 percent annually through 2010, iSuppli estimates. Besides health care, other growth markets include drug and genetic research, oil and gas, mining, and architecture. In each, the sales opportunity depends on factors such as whether 3D can improve productivity and if that industry has already moved toward other technologies that 3D can complement, such as digital imaging.

“We’ve had a lot of success in geospatial intelligence and photogrammetry, where they can’t do their job without a stereo monitor,” Robinson says. “It’s not a matter of whether it adds value. They have to have it. Previously, they were using just photographs with these complex machines to view them in stereo. Now they’re going digital.”

Whether 3D visualizations systems are affordable depends on budget and the display’s size and features. Autostereoscopic systems for applications such as health care start around $5,000 per display, Colegrove says, with large-scale, heavily customized solutions running into five, six, or even seven figures. “At one conference, a doctor said that the price is still quite high, even for hospitals,” Colegrove adds.

But ironically, some analysts say cost is the main reason why 3D has made more inroads in the consumer market than the enterprise space.

“On the flat-panel [autostereoscopic] side, the price is kind of high, so they’re targeting medical, science, and military because they can afford it,” says Colegrove, who has a report on the 3D market due out this summer.“On the goggles [stereoscopic] side, a lot of those are already targeting the consumer side. They’re selling for $1,000 or a couple hundred dollars.”

That’s noteworthy because the more experiences consumers have with 3D — preferably good experiences with no eye fatigue or nausea — the more comfortable they’ll be with using 3D in the work-place. One place consumers are likely to encounter 3D on a regular basis is the movie theater. In December 2007, Imax and AMC Entertainment announced that they’re teaming up to open 100 Imax theaters, a move that would double the number of 3D theaters in the U.S. Meanwhile, major filmmakers, such as Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson, are directing or producing 3D films.

MAKING THE BUSINESS CASE

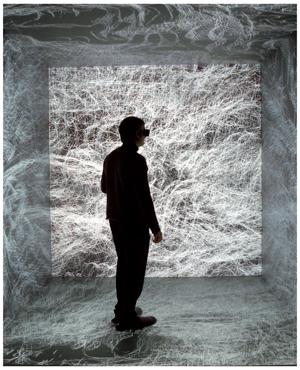

Geoscientists at the University of Calgary use Barco’s moveable virtual environment (MoVE) to locate oil and gas reserves faster and more accurately to improve productivity.

“>

Geoscientists at the University of Calgary use Barco’s moveable virtual environment (MoVE) to locate oil and gas reserves faster and more accurately to improve productivity.

Credit: Barco

The architectural industry seems to be a perfect fit for harnessing the power of 3D technology. At the Louisiana Immersive Technologies Enterprise (LITE) facility in Lafayette, architectural firms can use a variety of 3D and supercomputing systems for designing buildings. The $27 million, 70,000-square-foot facility opened in September 2006 and features 3D equipment including the stereoscopic DLP-based Mirage projection system from Christie Digital Systems, based in Cypress, Calif.

“Instead of looking at the typical materials that an architectural firm provides — some animation, maybe some small-scale models — they use our visualization technology to have a full, 1:1-scale walkthrough in 3D stereo through a proposed building,” says Dr. Carolina Cruz-Neira, executive director and chief scientist at LITE. “That’s much easier for the people trying to make a decision because they get to be in the building before it’s built.”

LITE’s facility highlights some of the costs and savings that enterprises can expect when implementing 3D. At LITE, architects can run their 3D models through scenarios, such as floods and fires, and actually see the impact. Structural problems caught at that stage are easier and less expensive to fix than when they’re literally set in stone.

One user told Cruz-Neira that the traditional mix of physical models and 2D renderings typically added about $1 million to a project’s cost. “Now, with this technology, the $1 million has turned into not even $100,000,” Cruz-Neira says. “There are significant savings in doing it this way.”

But $100,000 is still a significant cost for most businesses. One reason for that steep up-front cost is that 3D display technology is still a niche play that often requires custom work.

“There’s not a lot of off-the-shelf technology that’s ready to be applied in the context of building [design], medical, or oil and gas,” Cruz-Neira says. “It’s a field that’s very new … . A lot of the projects we do are one-of-a-kind.”

Those costs can be a show-stopper for some potential 3D users, Cruz-Neira suggests. Others agree that cost often is a barrier, especially for more than a bare-bones system. “There has to be a business case that goes along with it,” says Planar’s Robinson. “That may be one reason why 3D hasn’t taken off as much. [The integrator will] come up with a 3D visualization system that kind of works, but it costs $45,000.”

Manufacturers and integrators have a few options for getting over that hump. One is to show that clients can achieve a return on investment (ROI) sooner rather than later. But calculating the payback often requires knowledge of a particular industry vertical and, in turn, highlights the value of partnering with a manufacturer that’s already a major player in that sector. Their knowledge of how companies do things and how 3D could streamline those processes can help AV manufacturers and integrators sell to that market.

Another option is to send clients to a neutral facility where they can try multiple 3D systems and get a sense of which product features are “must-haves” versus “nice-to-haves.” LITE’s facility features seven different levels of 3D systems, ranging from $150,000 to $5 million. “They can do a minimal-risk trial of the technology and understand the different levels of technology and find out which is the right level for them,” Cruz-Neira says. “I’ve seen a lot of companies that have been misled into the ‘wow’ factor and have gotten more than they need.”

EASY ON THE EYES

Not surprisingly, manufacturers and users agree that the viewing experience often is another make-or-break consideration. If the 3D system creates eye fatigue or nausea, then it’s probably not going to be used as often as it could be — if it’s purchased at all — thereby undermining employee productivity. Those problems were common with some 3D systems, such as those using cathode-ray tube (CRT) technology. “A lot of customers who use CRTs don’t like the flicker,” Robinson says. “It gives them headaches and eye fatigue, and even makes them nauseous.”

Planar sees that market perception as an opportunity, at least when selling to companies that currently use CRT-based systems.

“Planar stepped in with stereo monitors because we didn’t necessarily have to convince them of the benefit of using stereo 3D,” Robinson says. “We just needed to show them an LCD-based stereo monitor that’s more comfortable to use, and the image quality is much better. You can do a lot higher resolution, and there’s no flicker, so you don’t get eye fatigue.”

That’s also an example of how today’s systems are replacing older 3D systems rather than just displacing 2D technologies.

“[Now] there’s a lot of technology put into it to make it very affordable,” Colegrove says. “They’re not replacing any other [technologies]. They’re replacing themselves — their earlier versions.”

Tim Kridel is a freelance telecom and technology writer based in Columbia, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].