Video Serves Those Who Served

The Military Advanced Training Center (MATC) at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., opened last September. Among its facilities was the Center for Performance and Clinical Research, known as the Gait Lab, where physical therapists and engineers study patients’ walking motions to gauge how rehab and prosthetics could help.

WHEN THE MILITARY ADVANCED Training Center (MATC) at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., opened last September, it met a long-standing clinical need that had become increasingly urgent: the need for a facility to rehabilitate returning soldiers who had lost limbs, suffered impaired limb function, or sustained brain injuries in Iraq and Afghanistan. Among its facilities was the Center for Performance and Clinical Research, known as the Gait Lab, where physical therapists and engineers study patients’ walking motions to gauge how rehab and prosthetics could help.

The old Gait Lab was a retrofitted square room, 28 feet by 28 feet, with eight motion-capture cameras mounted on walls and desks. The actual walkway for patients was about 25 feet long, says Brian Baum, a Gait Lab biomechanist. When Congress approved $10 million for the project in 2004, the project was awarded as a design/build to Turner Construction Co. and architecture firm Ellerbe Becket. Baum and his colleagues saw the chance to draw up a wish list for their new lab.

They wanted the lab to sit on an isolated slab of concrete, so that vibrations from surrounding rooms wouldn’t affect their patients’ motions (or how they calibrated them). They wanted more space, so patients could walk briskly, even run. They wanted a higher ceiling, so cameras could be mounted higher to give a bird’s-eye view. And they wanted better equipment.

Pouring the isolated slab was the first step. “We designed a special floating slab for the Gait Lab, dropped down about 6 feet,” says Tom Anglim, director of government services at Ellerbe Becket, who served as its project director on MATC. The extra space was needed for the six force plates that were installed in the floor to register how patients carry their weight as they walk, as well as for a treadmill with two more plates. The dimensions of the new room were set at 48 feet 10 inches by 34 feet 5 inches, with an 18-foot ceiling, says Baum. “Size and ceiling height are, from an architectural standpoint, basic things, but they afford us so much more flexibility,” he says.

When it came to specifying the new cameras, computer hardware and software, and force plates, the lab technicians were in the driver’s seat, says Elihu Hirsch, project manager for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. “They told us what the requirements would be as far as control wiring and wiring to cameras and monitors—they were able to communicate that to us with a sketch.”

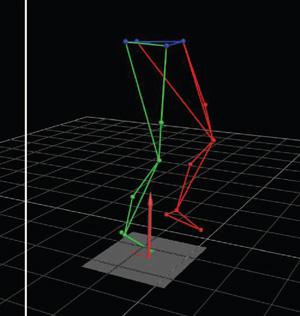

The 23 cameras in the new lab are mounted to an aluminum truss system that can be adjusted up or down. Baum and his colleagues chose Vicon MX-F40 motion-capture cameras commonly used in medical applications and movie animation. The cameras communicate via cable with the control computer, which uses a software program called Nexus, also made by Vicon, to capture the 2D views from the 23 cameras and turn them into a single, composite, 3D image.

“Each camera has a strobe of LED lights around it that flash a particular frequency,” explains Baum. “Every time they flash out, the flash hits a marker [on the patient’s body] that’s covered in special reflective tape. If the strobe flashes out 120 times per second, we can get the position of a marker in that camera view every 120th of a second.” With 4-megapixel resolution, the new cameras are a big upgrade from those they replaced.

Baum is excited about the new lab’s research potential, especially the new video cameras. “They allow us to see the same-sized marker farther away or use much smaller markers at the same distance—we can model motion in a lot more detail,” he says.

This article originally appeared in PRO AV’s sister publication, ARCHITECT. For more, visit its Web site, www.architectmagazine.com.