The Dinkelspiel Auditorium on the campus of Stanford University badly needed better acoustics. In addition, students and performers wanted to make the room sound like a more popular venue on the campus— Stanford’s Bing Concert Hall—which was often booked. d&b audiotechnik had the answer to both these goals with their Soundscape system. Kevin Sweetser who was the audio consultant on the project and Nick Malgieri who does support for d&b are here to talk about it.

SVC: Let’s start with you, Kevin. What’s your background on this project and how did you come into it?

Kevin Sweetser: I was actually the production coordinator for the Stanford Department of Music for about five years. In that time, I was in charge of the venue and a lot of the upkeep and future proposals to bring things to the venue. We did about 200 shows a year in the venue so I was quite familiar with all the sound needs and all the ins and outs of it.

You were the audio consultant on this project.

Kevin: Yeah, I proposed this whole project while I was still employed through the university. We actually got approval as I was deciding to leave – I have moved across the country. So I proposed the system and I explained the benefits of having a turnkey system that anybody could use–and that would fix these acoustics that everybody had been complaining about.

So you have the experience with the venue on the one side and then on the other side we’ve got Nick Malgieri from d&b audiotechnik who is the expert on the Soundscape system. Nick you’re with Education and Application Support—what does that job involve?

So you have the experience with the venue on the one side and then on the other side we’ve got Nick Malgieri from d&b audiotechnik who is the expert on the Soundscape system. Nick you’re with Education and Application Support—what does that job involve?

Nick Malgieri: I do kind of 75 percent of pro-active support- -things like consulting on system designs and training for our workshops at our d&b facilities, or workshops onsite at a venue. The rest of my job is more reactive support; the nights and weekends helping to bail people out of a tough situation if they have any technical issues during an event.

The Dinkelspiel Auditorium at Stanford is very popular with the local performers and musicians but it’s not a real big place.

Nick: Yeah. We have about 710 seats in a kind of a raked-wide style. So the auditorium is not very deep, but it’s extra-wide and it’s a bit older as well. The building was built in the 1950s and was originally intended to have an organ in the loft, so a lot of the acoustics in the building were designed with that in mind.

There are a wide variety of things that go on in there, not just one type of music or events.

Nick: Correct. It’s one of the bigger facilities available for students so we get a lot of student groups as well as music shows. We get everything from dance groups to some touring groups, some music, some theater. We also do some talking-head presentations and community events, in addition to our normal department music shows with jazz, chamber music – it’s all over the map.

There were two Soundscape systems installed in this same venue. I don’t think I’ve heard of that before. Why two Soundscape systems in the same place?

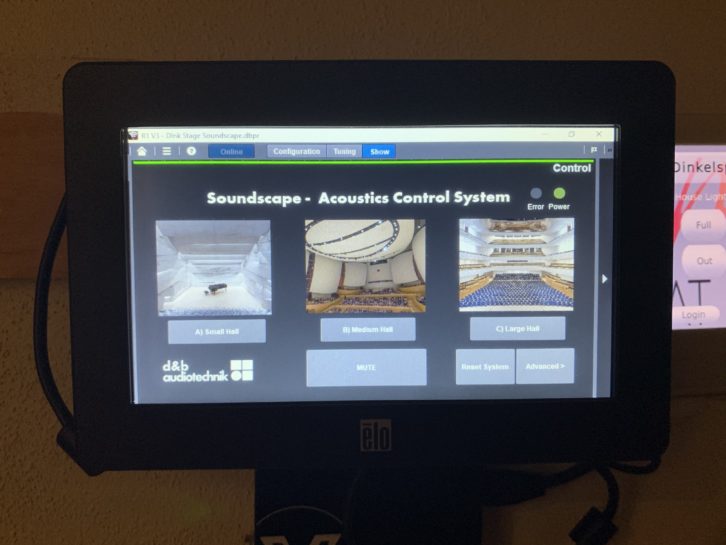

Nick: The two systems operate in two different discreet manners. One actually covers the audience area and what we would consider a typical Soundscape environment and that’s operated by a sound engineer working a mixer. Then the second system powers a system over the stage. That system is working as a virtual orchestra shell and controlled by a touch screen on the side of the stage. It can be activated and controlled by your average non-technical user, such as a music director for an ensemble, to be able to recreate the acoustics of concert halls without needing a technical person onsite. The touch screen itself really only allows them on/ off and three different acoustic spaces that can be modeled. Those processing algorithms are fed by suspended microphones over the stage; no one even needs to deploy a microphone on an instrument for it to work.

Nick: The two systems operate in two different discreet manners. One actually covers the audience area and what we would consider a typical Soundscape environment and that’s operated by a sound engineer working a mixer. Then the second system powers a system over the stage. That system is working as a virtual orchestra shell and controlled by a touch screen on the side of the stage. It can be activated and controlled by your average non-technical user, such as a music director for an ensemble, to be able to recreate the acoustics of concert halls without needing a technical person onsite. The touch screen itself really only allows them on/ off and three different acoustic spaces that can be modeled. Those processing algorithms are fed by suspended microphones over the stage; no one even needs to deploy a microphone on an instrument for it to work.

Nick, how does the Soundscape system work? The general concept, and then take us into the components of it.

Nick: Sure. So the hardware for the system is called the DS100. This is a 64 input/64 output audio processor. It handles all of its I/O via Dante. This processor by itself works as a matrix mixer, 64 inputs to 64 outputs in any combination, including level and delay, at the matrix crosspoints. From there we have two optional software packages. The first one is called En-Scene, and this enables what we refer to as object-based mixing where each signal into the processor is associated with an icon on the screen. Whenever you position that icon, the entire sound system realigns to amplify that signal but reinforce that object’s position. It’s going to work for up to 64 objects at the same time. Each object can be a single microphone or a group of microphones as desired. The second software option is called En-Space and this is emulated room acoustics. So some of our clever R&D folks have traveled the world to some of the most desirable acoustic environments, taken a large number of impulse-response measurements. They then enabled these impulse response measurements to be applied to speaker deployments in a way that recreates the location of the initial impulse response measurements. This allows us to quickly and easily emulate the room acoustics of a desired space in another. All of this happens almost automatically because in the d&b world our system design comes from ArrayCalc. An ArrayCalc knows the location of speakers. So once we go online with the processor, the processor then knows the speaker locations and can automatically apply the algorithms as needed.

OK, sort of like taking an acoustic fingerprint of the room and then pressing that down onto another completely different room to make it sound the same.

Nick: Yeah, that’s a great analogy

Kevin, when Nick first explained this system to you what was your first impression?

Kevin: The idea of being able to copy a space and bring it somewhere else with relative ease was immediately exciting. That we could also change the acoustics instantaneously, was very interesting. We have a lot of people at Stanford that are very interested in room acoustics up at the Center for Computer in Music Research we know as CCRMA. But the object-based mixing was a really cool idea in terms of trying to give a transparent feel to the sound, which is something that especially I feel music folks and audiences really like– that impression of just not being able to notice the PA. I only saw a demo, but it was very true.

Kevin: The idea of being able to copy a space and bring it somewhere else with relative ease was immediately exciting. That we could also change the acoustics instantaneously, was very interesting. We have a lot of people at Stanford that are very interested in room acoustics up at the Center for Computer in Music Research we know as CCRMA. But the object-based mixing was a really cool idea in terms of trying to give a transparent feel to the sound, which is something that especially I feel music folks and audiences really like– that impression of just not being able to notice the PA. I only saw a demo, but it was very true.

How many microphones were used in this particular installation?

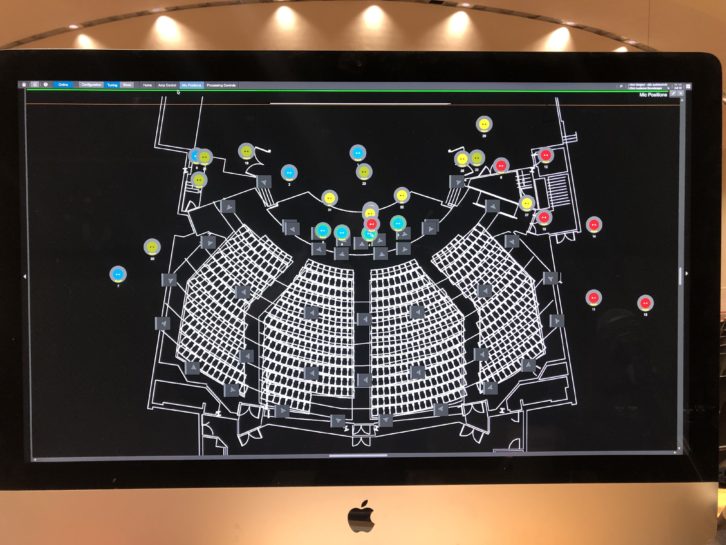

Nick: We have 23 microphones, 15 of which are over the stage area and eight of which are in the audience.

And those are shared between the onstage and house systems?

Kevin: Yeah, they are. I think Nick can explain this a little bit better, but the EnSpace system is taking both microphones above itself and ones on stage, and some of the ones in the audience too, to recreate the room acoustics for the folks on stage. And the audience system is doing almost the inverse. So it’s using the microphones on stage to amplify that, and the audience ones to give you that immersive feel.

Where did you put the various physical components of it as far as the processing and everything?

Kevin: We have an older amp room, which we tore out basically completely. It had some original amp racks and some processors from probably the ‘60s or ‘70s when it was put in. That room got completely transformed, and the room next to it, because we went from one rack unit to four with all the multiprocessing and amps we’re using. The microphones themselves we actually had to place over the stage pretty carefully because there are a lot of things in the building already. We had to go through and make sure that all the microphones would not be hitting existing lighting instruments or HVAC. There are a lot of different things playing into it, but the microphones ended up all pretty dispersed in a pretty even pattern across the stage and around the audience. We tried to pick up as much as we could in each of the zones, splitting it up into four sections and then just dividing that equally.

Maybe that could present some challenges for the lighting, too, as far as the shadows of mics and mic cables on the stage.

Kevin: Luckily, the venue, with all of its oddities, is actually really short. It’s only 18 feet from the floor to the top-most plaster on stage so we didn’t have to drop the microphones down too far. And so the venue’s lighting almost makes it unnoticeable and the cables are pretty thin. You see little microphones capsules every once in a while, but it wasn’t too much of a hindrance on the facility.

Kevin: Luckily, the venue, with all of its oddities, is actually really short. It’s only 18 feet from the floor to the top-most plaster on stage so we didn’t have to drop the microphones down too far. And so the venue’s lighting almost makes it unnoticeable and the cables are pretty thin. You see little microphones capsules every once in a while, but it wasn’t too much of a hindrance on the facility.

This is a very busy performance room so Kevin, what was your timeline on getting all of this in and working?

Kevin: The timeline was actually relatively short for actual install but we had a lot of planning on the front side of it. We’d been planning and designing this project for about two or three years. But on install we had a matter of a few months to completely renovate this building with new audio lines, microphones and speakers going everywhere. We had to work in between the school schedule, which is extremely busy. I think we had about a month and a half that we blocked out of our schedule, one month in fall and then we did another little install this spring as well to finish off some things.

Who helped out on the project and did some of the hands dirty work on it?

Kevin: A great company out of Sacramento called Alive Media was our AV integrator on this one. They took a lot of our designs, and we presented them with all these packages of 108 speakers and all the 23 microphones that we wanted to use. In very little time they were actually able to help us come out with a quick design plan and they were really, really great to work with.

When it got to the physical installation stage what did you have to do first?

Nick: You know, I worked with Kevin over the course of the conceptualization period for the project. We talked about many design reviews and as more use cases popped up we revised the design as necessary. And then we brought Audio West into the fold; they’re a d&b partner. They helped supply and furnish the equipment to Alive, who was working as the integrator. Between Audio West and Alive they did a great job of getting all of this stuff wired and mounted. Once I came into the program, it was really just an issue of updating the ArrayCalc software to match any minor position changes that had happened with speakers. Of course you can design that in the software all day long, but the speaker goes wherever there’s a stud that can mount it or wherever there isn’t an exit sign or all the other logistical considerations. So we just update the software with the exact speaker positions and then at that point most of the programming is finished.

I understand that in addition to optimizing the unusual space of the Dinkelspiel Auditorium, you were also trying to have it sound more like the nearby Bing Concert Hall?

Kevin: Yeah, that was pretty much exactly it. The Bing is a newer venue on campus. A lot of the music faculty and staff have shows over there. It’s a beautiful building with acoustics that are desired by a lot of them. So when we talk about having events back at Dinkelspiel, which is actually owned and operated by the department, they are underwhelmed, to say the least. One of the things that won us this project was that ability to recreate a fingerprint of another building. Since so many people liked the sound of Bing Concert Hall we were actually able to work with d&b and they modeled Bing and added it to their library. We were then able to use that software in Dinkelspiel.

That made a lot of the performers happy I’m sure, giving them the acoustics they preferred.

That made a lot of the performers happy I’m sure, giving them the acoustics they preferred.

Kevin: Yeah. And an added benefit and use case actually came up. The Bing’s calendar was getting more and more compacted. So rehearsals were becoming harder to come by. Being able to rehearse at Dinkelspiel, in a space that sounds very similar, was a large benefit.

This has got to be a very immersive system so tell me about the speakers?

Kevin: The speakers are pretty much everywhere. We have a large fleet of speakers overhead in both the stage and audience area and as well as a full fleet of surrounds, which is the main powering force of the Soundscape DS100. There are surrounds basically everywhere in the building, I’d say spaced about almost 15-20 feet apart from each other going around all edges. Even on the back of the stage, we have some behind our cyclorama there, firing through it. And then there are the mains, of course, for the audience, which are just mounted on the lip of the stage, hanging pointed straight at the audience.

That involved a range of different speaker models I would guess.

Kevin: Yeah, that’s correct. Like we talked about, the building is a little bit on the smaller side for what it is, so we actually deployed a large fleet of installed little 5S speakers paired back-to-back. It’s a design that Nick and d&b came up with to create a more universally distributed system overhead. We have a lot of column speakers that are actually all surrounds. For our mains we have D10s; they can be transformed from a distributed Soundscape system, which is six speakers across the front, or they can be taken down and rehung as a left/right/center PA.

How does the R1 control software work?

Nick: We built a couple of custom remote views for the users to simplify the controls for the average engineer who comes in. The engineers vary a fair amount on their experience levels, so we just needed to keep it simple. Essentially, it’s two pages. One page handles all of the audio objects – so for each microphone that comes into the mixer the operator can move the sound object to represent where that performer is located on stage. This means that all of the audio coming out of the system localizes to where that performer is visually. And, also, the whole sound system time aligns to that acoustic source on stage, helping it sound transparent. The second page controls the send level of each of the inputs to the En-Space emulated room acoustics. So even though it’s a three-dimensional fingerprint of the acoustics of another space, it can be controlled just as easily as a reverb on an AUX.

Do you perform any type of multitrack recording?

Kevin: On occasion we have. Generally for our shows we’re not recording anything too fancy, but we did try out a few shows recording multitrack from the console with really great results.

When the installation was complete, how did you handle the testing?

Nick: Definitely this use case was a little bit different for us and how Soundscape was originally pictured to be used. So Kevin and I made sure that we gave ourselves a couple of extra days just to play around and feel out the system and experience its capabilities before we settled into the final programming.

I’m sure this is fun to demo. It must really knock people over then they hear it and then within a few seconds it’s like they’ve walked into a whole different venue.

Nick: Yes Kevin and Stanford were gracious about allowing us to demo for the community, which we did for all kinds of use cases. One of the things we talked about in those demos was corporate events. I think two of the main takeaways for those users was first, the ability to design your speaker deployment differently, which allows a higher quantity of smaller loudspeakers. That has sightline and logistical rigging benefits, particularly with corporate events that have large video imagery. And the second was to be able to utilize the object-based mixing to mitigate problems with feedback, which of course with corporate events, with lavaliers and lectern mics, is a major concern.

Nick: Yes Kevin and Stanford were gracious about allowing us to demo for the community, which we did for all kinds of use cases. One of the things we talked about in those demos was corporate events. I think two of the main takeaways for those users was first, the ability to design your speaker deployment differently, which allows a higher quantity of smaller loudspeakers. That has sightline and logistical rigging benefits, particularly with corporate events that have large video imagery. And the second was to be able to utilize the object-based mixing to mitigate problems with feedback, which of course with corporate events, with lavaliers and lectern mics, is a major concern.

Yes and I would think that when you have a performer who wants to carry a mic out into the audience that’s a challenge on the feedback end, too.

Nick: Yeah, of course. In one of the very first shows for Stanford Jazz Workshop, they had a performer enter from the rear audience doors and come down through the audience to the stage. They were able to track him in real time using the sound object on the screen.

It’s got to be great to have such a flexible sound environment, with the ability to go from a spoken word lecture to a stage full of musicians and making them both sound right, and being able to switch from one to the other with just the push of a button.

Nick: Yeah, that’s right. The object-based mixing and emulated room acoustics are a paradigm shift for so many people, especially non-technical people, I think it was important for us to just show this new approach to live sound so that people could wrap their minds around it. And then the exciting part will be to see after the first year where people go with this technology and how their performances evolve now that they have our capabilities.